“Oh my God, not another one.” – Mrs. B Church

That’s the thing about leaving the big studios and setting up shop in a converted NYC bedroom, I guess. Not that my wife could tell you what any of my gear is or what it does in the context of producing music. Or that she cares, despite my occasional excited demonstrations. But splurge for so much as a new set of fancy 500 series thumb screws and she’ll smell the UPS truck from a zip code away.

Her “ugh, it’s your money” groan trailed off into Miss Othmar’s trombone disdain while I disappeared behind my already-stuffed-full rack of vintage and vintage-inspired gear in search of two free channels to send to-and-fro my packed-to-the-gills interface. Seriously, a 32×32 converter might seem like overkill to most in these in-the-box times, but I’m using nearly all of it.

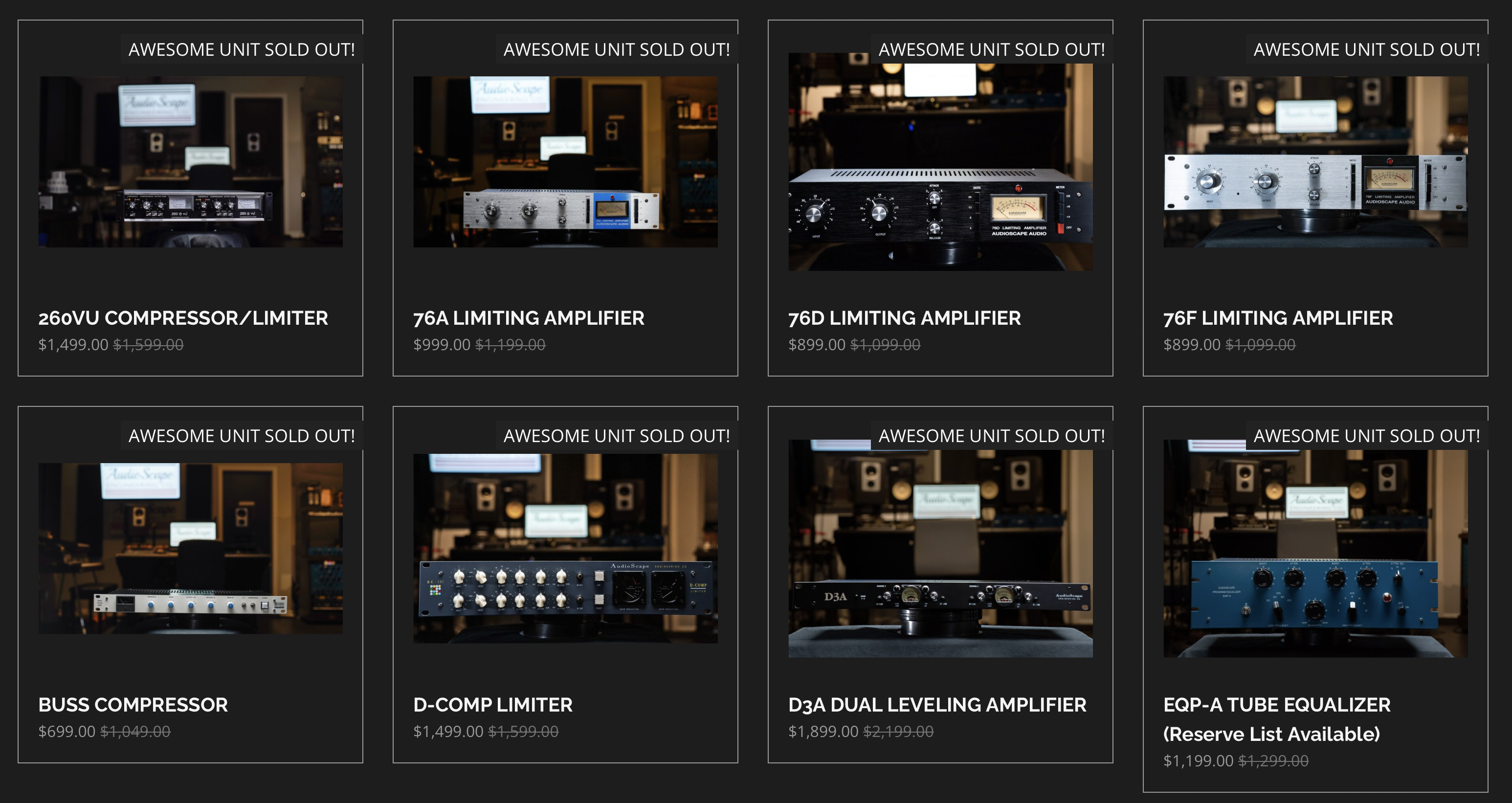

DO YOU EVEN AUDIOSCAPE, BRO?

Floridian bespoke makers AudioScape have been steadily cementing a very lucrative niche in the music production world. While they’re certainly not the only boat in the ‘vintage revival’ ocean, their products are handcrafted in small batches with love and attention to detail. Oh, and an uncanny ability to meet the market at the kind of price point normally occupied by units mass-produced halfway around the planet.

And while a sizeable portion of their portfolio offers excellent recreations of stalwart studio greats (just in case the rock you threw five feet missed the other G-Comp and LA-2A clones out there), they’ve got a few pieces that take inspiration from where the technology’s been to build something that can truly define where we need it to go.

THE D-COMP: DYNAMICS IN A D-CUP

AudioScape’s DC-101 “D-Comp” ventures off into a place a bit more its own. From a 10,000-foot vantage point, the D-Comp is a dual-mono/stereo-linkable compressor/limiter based on four hand-matched pairs of zener diodes. Diode bridge compressors, like the Heritage Successor we reviewed earlier this year, are a much-less-common topology compared to VCA’s or optical attenuators.

Why? In this modern day where we tend to buy analog outboard more for character than utility, that’s a fair question. Because, like the even more-ignored PWM compressor sound, nothing really sounds quite like these chest-beating tone machines. Zener compressors can not only clamp down on transient-rich material faster than a feral cat at a bird feeder, but they do so with a distinctive attitude uniquely their own. The goal may have been transparency in their 60’s/70’s salad days- but that’s not what happened. Call it ‘mojo’ if you want. I don’t. But you can.

Where the Successor is a modernized stereo-only Neve 2254 with many excellent nice-to-haves like multiple hi-, low-, and even notch-filters before the sidechain and a parallel blend control, the D-Comp seems to have taken some inspiration from the hallowed EMI TG124 design used famously in Abbey Road Studios’ golden era. This original design was chasing after a similar sound to the Fairchild 670, using diodes in place of the EZ-Bake Oven amount of tubes.

Back here on Earth, the D-Comp does its will as it is in Fairchild/EMI Heaven closer to the Chandler TG-1. But like the aforementioned Heritage, the addition of several key features open up an entire new set of controls and tonal options – expanding the list to a much, much wider set of potential applications.

MEETING MY ONLINE HOOKUP

Even getting your grubby little mitts on an AudioScape anything takes a little more than a PayPal account and a young cowboy’s smile. Here in NYC, there’s a bakery that has chocolate croissants that are, and this is not for the lack of a better word, orgasmic. Thing is, everyone from within about three subway stops knows this and you’ve got to be there, patiently waiting in line on a Sunday morning at 9AM sharp to get one.

That’s a quite similar experience, actually. AudioScape produces small batches, all hand-wired and assembled right in the Floridian swampland of guns, flags, and bald eagles. Feedin’ time begins promptly at 8:00PM every Wednesday and Saturday night and whatever they’ve got is going to be sold. Quickly. And if you aren’t reloading their page with your payment information ready to go, you’re going to miss out. We’ll call it “part of the fun” – just know it’s not as simple as a trip to Sweetwater.

Pulling the DC-101 from its cardboard confines, I was immediately struck by the handsome, sturdy build. Across the board, every corner, knob, and connector felt solid and in it for the long haul. A chonker of an external power supply filled me with confidence that there would be headroom to burn (and less heat inside my admittedly tight amount of rack space). With the Neutrik connectors clicked into place, I hit that jolly square power lozenge and ceremoniously cracked my knuckles to see what the buzz has been all about.

CONTROL FREAKS REJOICE!

Scanning the DC-101’s gun-metal grey 2U housing, you’re greeted with a matching top and bottom set of Bakelite-inspired chicken-head knobs, in/out toggles, and a pair of utility push buttons for power and stereo-linking that seem to have fallen off of an SSL delivery truck. Oh, and a bookmatched pair of nice big, backlit gain reduction ‘eyebrow’ VU meters for those of us who like our eyes to back up our ears.

The controls are stepped where they need to be, and continuous where they don’t (but I wouldn’t complain if they were). The independent input pots go from a non-descript zero to ten, which absent a threshold pot you use to set the amount of compression or limiting. Speaking of, that’s the next stop to the right, where you select either ‘out’, ‘comp’, or ‘limit’. The first is for simply giving your uninspired audio a trip through the D-Comp’s input and output stages, soaking up the magnetism of the Cinemag balancing transformers.

Select “comp” for a gentler ratio which, though not indicated in the admittedly sparse documentation, sounds about like a 2:1 or 3:1 ratio under normal use. And, as you probably had guessed, thwacking that dial over to ‘limit’ tightens the leash up to a much more spanky ratio in the 20:1 range.

Next stop along the way is a six-position control for inserting a sidechain hipass filter with points at 0 (off), 40, 80, 120, 200, and 320hz. This gives you tremendous agency to keep kick (or even snare) drums, bass fundamentals, or those basement-dwelling 808 notes out of the comparator, letting the D-Comp tighten up the octaves the listener hears, while leaving the part the listener feels rumble on.

There’s no one-size-fits-all here, and often toggling one click to the left or the right, even if you think you’ve set it correctly, reveals a different sound that might just be a wee bit better. I try (try) to not mix mathematically, even in this latter-day era of being able to key in frequencies to the fraction. This is a box that is far more rewarding for those who are working with their ears.

You’ve got output levels on a continuous (not stepped, mad face emoji…) control. If you’re looking to simply bake your tracks with the D-Comp’s internals, this comes in tremendously handy – letting you drive the inputs into deep red without crushing your converter or console return on the way back. Keep a grease pencil handy – unfortunately that’s how a unit like this manages user settings. Welcome to analog, kids.

To the right of the output stage is an 11-step control for attack times. Again, the D-Comp is light on the actual values in both use and documentation. My grizzled old ears would offer that those clicks go clockwise from “mere picoseconds” to “lazy Sunday drive”.

And finally, oddly, the release times are continuous and not indicated in any tangible way in terms of value. So close your eyes, push the unit into audible pumping, find the time that works, then back off the inputs. Voila. Just like grandpappy used to do.

Each channel offers its own in/out toggle, using two hands to do both at once would be kind of maddening if I wasn’t controlling the bypass from my DAW (but makes plenty of sense for dual mono operation). The aforementioned “link” and power buttons and those big eyebrow vertical VU’s round out the package.

I do have to point out the irony that, though things like db, ratio, and milliseconds are completely absent anywhere on the DC-101’s faceplate, both VU’s have “Gain Reduction” written on them, right above where it says “Gain Reduction” under each one. A cum laude graduate of The School of Redundancy School. Does this matter? No. Describing what the knobs and blinking lights do is not the fun part of a piece of gear like this, anyways. We’re moving on.

FIRST STOP: POUNDTOWN

Let me just get this out of the way: if you never even so much as put the AudioScape D-Comp on anything OTHER than drums, you’d still be getting your money’s worth. And that’s not just due to its market-savvy $1499 price tag, either. The DC-101 takes to drums and percussion like a fat kid to birthday cake, with metaphorically similar results.

Applied sparingly, the spaces between the notes are teased back towards the front of the soundstage, letting your ears bathe in overtones and decays you thought the recording process had passed over. Shades of EMI Studios’ storied history begin to flicker in your head with every passing beat and bar. Those famously awesome drum sounds on Radiohead’s “OK Computer” are now available in a rack-mount configuration.

Not content with re-recreating the work of Geoff Emerick or Nigel Godrich? The D-Comp understands. Go ahead and push those input levels a little harder, let the needles plunge a little deeper, and your drum mix (or overheads, room mics, whatever…) become damn-near impenetrable. Even loops or programmed drums that once sounded like microwaved leftovers seem to find new life – bits of new sonic information that was written off long ago. As stated above, the D-Comp is more like chasing sound with a vintage Moog than the menu-driven Yamaha DX-7’s that supplanted it. Its rewards come more easily to those who twiddle, not program their way to the sweet spot.

You could be led to think that the AudioScape D-Comp is designed to be a “vintage flavor” based on its lineage. “Vintage” is one of those words that is truly in the ears of its beholder, however. But you needn’t be in a Lenny Kravitz Cover Band Cover Band to reap the benefits. I had just received my 10th anniversary vinyl repress of Basement’s massively overlooked “Colourmeinkindness” LP and was lost in the nuances of its pedalboard-gazing epic mix, thanks in no small part to an absolute beefcake drum sound. Very now. Very modern. And very much the sort of thing this compressor can dole out effortlessly.

With diode bridge compressors’ tendency to get ‘pumpy’, the sidechain HPF is a godsend – letting bass drums have as much or as little influence on the overall picture as you please. At its highest 320hz setting, most snare fundamentals will also avoid tripping the alarm as well. The fastest attack time seems to be almost ahead of the notes – though that’s scientifically impossible given the whole time-continuum thing, I could swear there was a crystal ball hidden somewhere inside.

You really can throw this at any source or sources and find a new sonic footprint. The D-Comp is transformative on both close mics and stereo pairs. I personally couldn’t take it OFF my stereo drum bus duties. Even with the meters matched to within 1db, bypassing the unit seemed to yank the very bones out of my mix. A pair of Coles 4038 ribbons that were about 20 feet out from the kit in a particularly live space run through this thing conjured images of Godzilla laying waste to Tokyo, breathing fire through its nostrils.

BASS. HOW LOW CAN IT GO?

Though the LA2A and dbx160 continue to be many the discerning ear’s ‘go-to’ for bass guitar, the AudioScape DC-101 can do some pretty amazing things here.

I was working on remixing a lesser-known poppy-ish, emo-sh, garage-ish band’s 2012 LP for a 10th anniversary release. It was literally brought to me on one of those antiquated all-in-one mixer/hard disk recorder things that replaced the personal four-track around the turn of the century (albeit with sixteen whole tracks and, luckily, an optical output). Having had nothing to do with the original recording, I wanted to preserve the unintentionally no-fi aesthetic that comes along with recording with $1000 of gear in a makeshift rehearsal space while also making the result a bit more tangible.

The conundrum? The bass guitar was overlooked, despite the playing and parts themselves adding a lot of counter-melody and weaving wonderfully with the drummer. It didn’t help that the entire signal chain was likely no more than the ¼” cable plugged right into the recorder’s input. That sinking feeling you get when you hear “we just DI’d the bass,” before receiving a project? This is what you’re cringing about.

I sent that wimpy DI’d signal out to a small guitar combo and returned both signals to each side of the D-Comp. Before I could even look at the settings, I was already in love. The secret? I was wailing on the inputs, the gain reduction meters reading “WTF?!?!” Backed off to something a bit more conservative (but still pretty slammed), everything just glued itself together wonderfully. Knowing full well I was going to want the unit back on drum duties, I printed the results to new tracks.

FULL-THROATED APPROVAL

Vocals through the D-Comp are an absolute joy. Though the law of simplicity would likely see most pulling this compressor in on a vocal submix – which it does wonderfully, gluing voices and notes together like fly paper with a wonderful shimmer – that’s just a scratch on the surface.

Still working on the aforementioned band’s demo-as-master recording, I was wrestling with making a single, solo vocal part feel both up at the front and situated amongst the rest of the mix (side note: As a card-carrying member of Generation X, I hail from the school of not making things sound “one part vocal, one part everything else”). I can’t imagine the original track was recorded with anything more than an SM57, which in of itself is not a problem. The fact the singer chose to perform the song while drunkenly wandering away from it was.

The fix? “Pimp My Compressor”. Or, in the less-than-immortal words of 2000’s Detroit rapper-turned-game-show-host Xzibit, “we heard you liked compression, so we put a compressor on the compressor.” Put another way, I patched the output from channel 1 into channel 2 and ‘double-pumped’ the performance much the same way many engineers I look up to use an LA2A into an 1176. Take the hard peaks off aggressively with the first channel, then let the second add a gentle push-pull glide with a long attack and release.

The fact that this approach brought out every reflection in the room in the process? Well… we call that “freeverb”.

Did it work? Infallibly. I sent off some “are we close yet?” mixes to the artist and they couldn’t believe what they were hearing. The vocals had presence and immediacy for the first time in the decade since the first CD hit the shelves. Oh, they liked the drums and bass quite a bit as well. This box really did put in work.

BUT CAN IT RIDE THE 2-BUS?

A lot has been written about what makes the perfect mix buss compressor. And there are many separate, oft-warring tribes of thought here. Johnny-In-The-Box might have eight plug-ins stacked up – compressing, then expanding, then saturating, then compressing, eq-ing, limiting, and widening (but seemingly never inserting a phase meter). Others prefer to handle those sorts of things in sub-groups, leaving the master fader to apply just the slightest bit of necessary polish.

Me? I’m somewhere in the middle. My two favorite hardware compressors for just a bit of gentle level-hugging in the final two channels are the Stam SA-4000-II or the Tegeler VTC (which I fawned over here not too long ago). Now, one is a modern take on a vintage design and the other is… wait, they’re both that, actually. So, with one being based on a VCA and the other on tubes, why not give the D-Comp’s zener network a shot?

To be honest, I never liked using the Neve 33609 (or any of the clones like my Successor) on mix buss duties. Too tubby. Too pokey. It just made things feel mushy and wrapped in a wet blanket. “Warm?” Sure. But dull.

But the D-Comp is a different animal. Much has been said about the EMI console’s seemingly magical abilities to spin lead into gold. However, all but a select few peoples’ experience in use is a plug-in approximation. And that’s fair, this is hardware that’s esoteric – even the Chandler TG-1 from where the D-Comp draws inspiration commands a fairly hefty price. Maybe not Fairchild 670 prices, but still… you can buy two DC-101’s for less than the Chandler (which doesn’t even come with a power supply) and still have plenty left over for more rack space and cables.

Anyways, my experience on 2-bus work was mostly good. Source dependent. Modern rap and metal mixes tend to be inorganically slammed to the tits with all kinds of digital look-ahead gazillion-band limiting where the sound of software being pushed to the 65th bit is de rigueur. And that is most certainly not what you use a unit like this for. BUT (and I like big buts, I cannot lie), that’s not to say the D-Comp can’t be part of the fun. Before (or after) you crush the last breath of life out of your precious dynamics, the AudioScape can warm up the chilling effect that all that digitosis imparts.

You needn’t even switch the compression in, just spike the the inputs a bit and let those transformers do the work. Or back off DigiCrushMaxMasterPro a few (or a few more) db and let the DC-101’s limiter snatch the back end of those big peaks. Point is, yes, it definitely does that. It may not be designed to do what the mastering-chains-of-the-damned can, but as part of this complete breakfast? I’d sooner send a piece of analog hardware in to add a bit of warmth and polish. Put another way, when somebody gets around to creating a plug-in version of the AudioScape D-Comp, I’m betting that the actual unit still wins in the final lap.

THE SATURATION FASCINATION

Just a quick aside here about using the DC-101 as a saturation unit. Yes, it totally does that. In fact, it can deliver the wooly goodness outstandingly well. But to my mind, it’s kind of like driving a Lambo to the grocery store. Drive those inputs like sled dogs, back your outputs off, and the D-Comp will give you full run of the transformers all you like. But, just so you’re aware, it’s got two lonely channels of world-class compression in bypass.

Frankly, the chatter on newbie-encrusted internet forums about saturating the saturated saturations is just the result of too many content-driven YouTube videos. A little bit of those Cinemag transformers can be… uh… transformative to otherwise brittle sources, yes. But I’m also reminded of Prince engineer Chuck Zwicky once showing me his “pigtail transformers”, where he just soldered a discarded Jensen JT-115 between two snipped ends of a spliced XLR cable. Because that works, too. And all for the total cost of a mic cable and a decommissioned piece of iron.

BUGS AND BUGS-AS-FEATURES

I don’t think there’s such a thing as a perfect piece of hardware or software, nor is there ‘one box to control them all’. Don’t get me wrong, there are some really great tools out there that are all but completely indispensable to my workflow. Some are expensive, some aren’t, but they do a certain thing in a best-in-class way for the sound I’m chasing.

My gripes are pretty minor here, especially when you realize just how much you’re getting and how good the D-Comp sounds. The lack of an external sidechain input is the lone half-star killer here, as a compressor that can pump like Hanz and Franz should be able to heave on command from any external source. And having stepped controls for release times and output level would really add an extra cherry on top of an already great dessert.

Paradoxically enough, I find the AudioScape D-Comp’s biggest bug to be its best feature. Whether it’s using the input levels to set the threshold or finding the right attack or release, you don’t “enter values” into the DC-101. You earball it with those weird semi-circles affixed to the side of your head. I even found the “gain reduction gain reduction gain reduction” metering a little off – what I was hearing didn’t seem to jive with what I was seeing.

Does that matter? Well to me, no, not much. For the decades I’ve spent using my thumb, forefinger, and ears to suss out the right EQ point, reverb tail, or compression ratio, the D-Comp represents a rewarding return to purity. Back when there were men among us who didn’t have presets. When you used a calculator to figure out delay times and soldered your own patchbays. I couldn’t help but picture myself on a paper towel roll package, chest hair protruding from my flannel shirt as I carried an entire winter’s worth of firewood on one shoulder. That’s right – the D-Comp made me feel (and my mixes sound) like a burly manly man’s man. Sorry, fellas. Even with the new compressor, Mrs. Church still likes me.

CLOSING THOUGHTS AND A GALAGANALOG

You can get a plug-in that approximates what the AudioScape D-Comp does for next-to-nothing. Hell, Analog Obsession has DSP solutions that are donationware that, to the casual listener, sound pretty close. And I get it, $1499 is considerably more than the change in your coat pocket.

But somebody in the production process has to be dissatisfied with “pretty close”. And we are that somebody. If you’re unable to hear the difference between the D-Comp and say… the Waves TG plug-in? Well, we can recommend some new monitors for you – or our handy multi-part guide to treating your mixing space. Because there is a difference in the way a circuit behaves and the way software emulates the way a circuit behaves. Maybe you don’t need that final 5% – but you owe it to yourself to hear the difference.

I’ll leave you with a strange analogy. I am a hardcore Galaga player, to the point of once having the actual circa-1983 cocktail cabinet in my studio’s lounge (I loved it when clients would crow about their prowess and challenge me – then have to negotiate off the hours of studio time while I racked up 2,000,000 points without losing a single ship). Anyways, the way the game is played with the original ROM chipset versus the way it’s emulated on modern consoles and PC’s is the difference between me hitting a world record and bombing out by stage ten. The differences to the outside observer are near-imperceptible, but to the person playing it, they’re vast.

That’s why there are those, and I count myself among them, who will always find just that extra juicy tidbit of awesome in the way electrical current flows through a circuit like the AudioScape D-Comp. Let Donny DSP and Vinny VST tell you there’s no difference all they want. They’re bringing boxing gloves to a fist fight.

Ultimately it’s your budget that dictates how much that extra little bit matters. For my money, $1499 of it to be exact (oh, yeah, I totally bought this), the AudioScape D-Comp is beyond a mere bargain. Even racked up against some serious competition, I can’t imagine a single situation where I couldn’t find a seat at the table for this amazing box.

• Far more flexible and versatile than its forebears.

• Solidly built by a solid US company from solid components.

• No external sidechain input. Bummer.

• Stepped controls across the board would've been nice.